Okay. Here’s a one regard in which Canadian food safety regulations beat their U.S. counterparts all-hollow. While Canadian Best Before / Expiry date labels are clear and unmistakable in their meaning, it seems that U.S. safety dating has left consumers there confused…

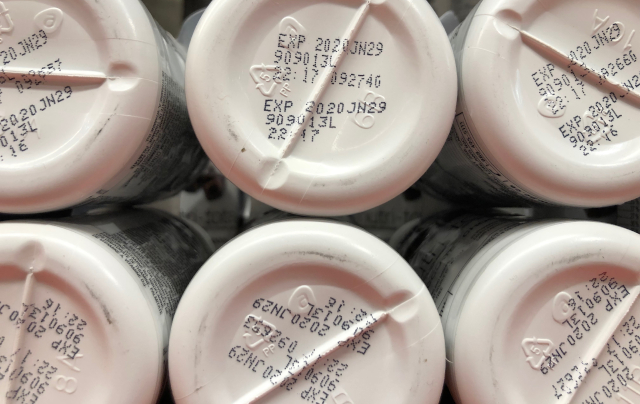

Canadian ‘Expiry Date’ label on a prescribed perishable

Canadian ‘Expiry Date’ label on a prescribed perishable

food product. Much clearer than the U.S. system…

Pretty clear, eh?

The Canadian system for ‘Best Before’ and ‘Expiry’ date food labeling could hardly be any clearer…

According to the PressBooks elecrtonic library: “The ‘Best Before’ date (or ‘meilleur avant’) as indicates the anticipated amount of time an unopened food product keeps its freshness, taste, nutritional value, or any other qualities claimed by the company, when stored properly. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (2018) indicates that unopened products “should be of high quality until the specified date.” As soon as the product is opened, the best before date no longer applies. The best before date must appear on packaged foods that have a shelf life of 90 days or less such as milk, yogurt, and bread. Products still can be purchased or eaten after best before dates as these dates are not related to product safety.”

In clear contrast: “Packaged foods that show an expiry date must be consumed before that date or discarded after the expiry date. The expiry date must not be mistaken for the best before date. Expiration dates are not required on all foods. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (2018) indicates that foods that have, ‘strict compositional and nutritional specifications,’ must have expiry dates (e.g., infant formula, meal replacements, nutritional supplements, formulated liquid diets for oral and tube feeding).

Not so transparent, huh?

However the U.S. system is just different enough to cause confusion among consumers – a lot of consumers – according to a recent study appearing in the May 6, 2021, edition of the Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior.

A poll of 2,607 subjects in the U.S. revealed that a majority of those asked did not know how to tell the difference between the two kinds of dates: ‘Best if Used By’ and ‘Use by’. In fact, the survey showed that only 46 percent of study respondents knew that the ‘BEST If Used By’ label specifically indicates that, though food quality (flavour, appearance, texture, etc.) may deteriorate after the date on the label. Less than 24 percent of respondents knew that the ‘USE By’ label means the food is not safe to eat after the date on the label.

“Our study showed that an overwhelming majority of consumers say that they use food date labels to make decisions about food and say they know what the labels mean,” Catherine Turvey, MPH, of The George Washington University, Washington, DC, told ScienceTechDaily (STD). “Despite confidently using date labels, many consumers misinterpreted the labels and continued to misunderstand even after reading educational messaging that explained the labels’ meaning.”

But the real shocker was still to come

“[Even] After viewing educational messages, 37 percent of consumers still did not understand the specific meaning of the ‘BEST If Used By’ label,” Turvey told STD. “And 48 percent did not understand the specific meaning of the ‘USE By’ label.

An interesting detail: The U.S system has recently been ‘streamlined’ in an attempt to make it more understandable(italics mine).

The takeaway

“Responses to the survey suggest that date labels are so familiar that some consumers believe they are boring, self-explanatory, or common sense despite misunderstanding the labels,” said Turvey. “Unwarranted confidence and the familiarity of date labels may make consumers less attentive to educational messaging that explains the food industry’s labeling system.”

Wow! That’s a recipe for mass food poisoning – or worse!

What to do?

Further education campaigns by government and non-profits are, the study concludes, needed to ensure that ‘more’ people know the meaning of the two kinds of food safety dates. How about ‘most’? Or ‘all’?

Anyway, the U.S. could have saved itself a huge problem by simply going with the Canadian system, or something equally clear and unmistakable. I guess Americans just have to be different.

~ Maggie J.