If you haven’t heard of ‘umami’ yet, you must have been lost in the deepest depths of the Amazon Jungle or someplace similar for the past decade… Today, we let you in on umami’s secrets. And explain how it can flavour-up even the blandest dishes!

Science to the rescue

Science has quantified the chemical and sensate aspects of the phenomenon. We know the molecular definition of umami, and can test boundless foods for its presence. Some foods in which it’s been found may surprise you!

What you taste

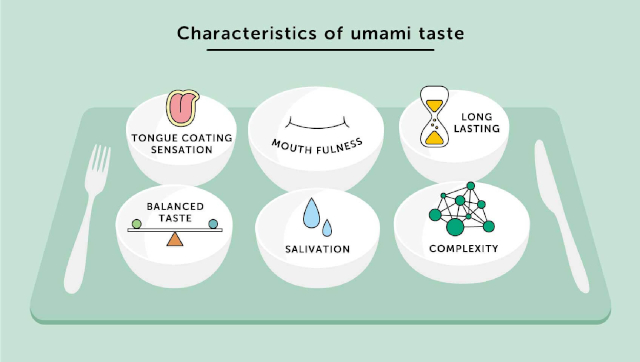

Earthy, musky, funky, meaty, savoury, seared, roasted, fermented, aged and more are words folks have used to describe the umami sensation on their palates. In fact, the seemingly complex umami experience is mediated by just two chemical compounds: amino acids glutamate and inosinate.

The Ajinomoto Group is a Japanese chemical company whose stated mission is, “contributing to the well-being of all human beings, our society and our planet with ‘AminoScience’.” That’s a fancy way of saying they’re in the umami business. (Most folks who’ve dined at Asian restaurants will immediately recognise their Panda logo! See photo, top of page.)

The ‘umami’ page at the Anjinomoto website describes the discovery of the ‘5th taste’, in 1908, thus:

“Umami was first identified by Japanese scientist Dr. Kikunae Ikeda. While enjoying a bowl of kelp broth called kombu dashi, he noticed that the savory flavor was distinct from the four basic tastes of sweet, sour, bitter, and salty. He named this additional taste ‘umami’, which literally means ‘essence of deliciousness’ in Japanese. Dr. Ikeda eventually found the taste of umami was attributed to glutamate.”

We’ve all experienced it

Red meat, cured meats, aged cheeses, tomatoes, onions mushrooms, salmon, sardines, anchovies, green tea and many more everyday foods naturally contain gultamate. Some also contain inosinate. Mushrooms, in addition, have a small amount of a third umami-related amino acid, guanylate.

How (you might say, ‘why?’) we experience umami was a mystery until 2002, when researchers identified specific umami receptors on our taste buds. It was only then that the world officially recognised umami as a true fundamental taste, along with sweet, sour, salt and bitter.

The salt connection

We all know that too much salt is bad for your arteries; a major cause of heart attacks and strokes. And the Anjiomoto folks are quick to poinbt out that their flagship product, monosodium glutamate (MSG), extracted from seaweed, is an ideal way to add umami to your recipes.

Yes, the ‘sodium’ in ‘monosodium’ is the same as that in salt. And the sodium, specifically, is the stuff at the root of the health issues around salt. But MSG is claimed to offer much greater flavour boosting power with less than 1/3 of the sodium in regular table salt. MSG is a is a much more complicated molecule than salt and works in different, additional ways on your tongue.

That makes it a potential dietary hero. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has set a goal for us all to reduce our total daily sodium intake by 30 percent. WHO estimates that would dramatically the reduce the incidence of high blood pressure and related cardio-pulmonary conditions. That would mean fewer deaths and hospitalizations from heart attack and stroke. And that would translate into billions of dollars in savings on health care.

But is MSG safe?

There have, over the years, been accusations leveled at MSG that it causes health issues. One of the most notorious claims was that the stuff caused headaches. Some Western diners said they experienced the headaches after eating Asian food in restaurtants. Thus, the affliction became commonly known as ‘Chinese Food Syndrome’.

Now, however, science has determined that the long-held belief that MSG was hazardous was more rooted in xenophobia than medicine.

Recent research has determined that only about 2 percent of folks who consume MSG suffer headaches. And those may be triggered by other causes. Researchers have since demonstrated that there is no clear and consistent causal relationship between MSG in restaurant foods and the symptoms described above.

Why use MSG?

Asian restaurateurs have traditionally used MSG to boost the natural umami quotient of their dishes. Some say that’s because Asian cuisines favour boldly flavoured, often highly spiced dishes. The more flavour the better!

I think – and this is purely speculation, based on my own experiences with traditional Asian food – that it has something to do with the way it’s served.

If you’ve ever dined in an Asian home where they eat the authnetic, old country way, you’ll know that they start with a healthy dollop of steamed white rice and top it with relatively small quantities of vegetables and proteins. All that bland, plain rice is bound to dilute the flavours of the meats and veggies on your palate. So you’d want to go with the most flavoursome toppers you could create!

On balance…

It seems as though umami – though only relatively recently defined – may be the most important of our basic tastes. And if it can contribute in a major way to helping us all reduce our salt intake, I say go for it!

~ Maggie J.